Let’s look at ‘Recovery’ in a deeper way; in a way that includes helping our culture recover a wider range of discourses on the nature of ‘madness’.

One of the most compelling pieces of research in Mental Health must be the World Health Organisation studies in the late 1960’s which were searching to find out if so-called ‘schizophrenia’ was common to all cultures. The surprising finding for me was not that psychotic experiences seemed to occur globally, but that the prognosis for people having these experiences was better in some of the ‘developing countries’ than in the ‘developed countries’ (Jablensky et al., 1992; 1994). The psychiatric journals by and large ignored this finding, focusing upon the universality of the psychotic experience instead to herald the apparent fact that ‘schizophrenia’ must therefore be a biological phenomenon, and therefore culture could be largely ignored. However, a few brave writers began to voice questions as to whether our approach in the western world is iatrogenic. Arthur Kleinman’s ‘Rethinking Psychiatry’ (1988) is a good read on this.

One of the most compelling pieces of research in Mental Health must be the World Health Organisation studies in the late 1960’s which were searching to find out if so-called ‘schizophrenia’ was common to all cultures. The surprising finding for me was not that psychotic experiences seemed to occur globally, but that the prognosis for people having these experiences was better in some of the ‘developing countries’ than in the ‘developed countries’ (Jablensky et al., 1992; 1994). The psychiatric journals by and large ignored this finding, focusing upon the universality of the psychotic experience instead to herald the apparent fact that ‘schizophrenia’ must therefore be a biological phenomenon, and therefore culture could be largely ignored. However, a few brave writers began to voice questions as to whether our approach in the western world is iatrogenic. Arthur Kleinman’s ‘Rethinking Psychiatry’ (1988) is a good read on this.

Kleinman, an anthropologist and psychiatrist at Harvard acknowledges those calling anthropology “the uncomfortable science” because it focuses the inquiry on the professionals themselves; and certainly these findings from the WHO studies do just that. He concludes that the dominance of biological psychiatry in Western society is due to no particular interest groups benefitting from defining “depression” and other such socially constructed “disorders” as social problems, in quite the same way as pharmaceutical companies and professional groups like doctors and nurses do in defining them as physical illnesses. As we shall see, in keeping with Foucault, he claims that the Western world view or ideological heritage of individualism and positivism would be threatened if we didn’t define these problems as individual problems, and limited the methods of cure to individual ones. This threat may well be seen in the assassination of Martin Luther King for expressing this view, including in a speech to the American Psychological Association (1968) just before his death; calling on us to see our clients as “coalmine canaries” in an unjust and sick society, rather than sick in themselves. He called for an international association for the advancement of creative maladjustment, for we should all be proud to be maladjusted, preferably in a creative way, to this unjust and sick world. That is not a claim we hear our professional bodies making, and indeed we might be accused of bringing the profession into disrepute for saying it.

Historian of ideas, Michel Foucault, traced the development of our modern ways of viewing ‘madness’; showing this to be inseparable from the ways we view ourselves, and the institutions we have developed that maintain these views. Today we recognise this as a social constructionist account. This is where our (mutually agreed) shared attention directing activities (which Wittgenstein called ‘language games’) create social realities, such as money. Money works to the degree we all agree to treat these pieces of metal and paper (the underlying ‘brute facts’) as having a certain value. Thus the WHO finding can be framed as saying that ‘psychosis’ is an underlying ‘brute fact’ common to all cultures, but how we relate to this lies in our shared attention directing activities. What’s more, the WHO findings show that the way we socially construct madness makes a difference to outcome, and we are not doing it as well as some simpler cultures. Thus the importance of Foucault’s analysis.

Historian of ideas, Michel Foucault, traced the development of our modern ways of viewing ‘madness’; showing this to be inseparable from the ways we view ourselves, and the institutions we have developed that maintain these views. Today we recognise this as a social constructionist account. This is where our (mutually agreed) shared attention directing activities (which Wittgenstein called ‘language games’) create social realities, such as money. Money works to the degree we all agree to treat these pieces of metal and paper (the underlying ‘brute facts’) as having a certain value. Thus the WHO finding can be framed as saying that ‘psychosis’ is an underlying ‘brute fact’ common to all cultures, but how we relate to this lies in our shared attention directing activities. What’s more, the WHO findings show that the way we socially construct madness makes a difference to outcome, and we are not doing it as well as some simpler cultures. Thus the importance of Foucault’s analysis.

Foucault’s analysis shows that since the Middle Ages our social construction of madness has been increasingly entwined, as various transformations of that view have occurred, in the social construction of ourselves. As we defined or constructed madness we defined ourselves as ‘sane’ or ‘normal’. So questions arise as to why it is so important to define ourselves as ‘sane’, or why has that become of increasing importance? Foucault’s work shows us that as industrialization occurred over the past four centuries or so, we became increasingly individualized and geographically mobilized, separated from our primary attachments. Understandably, anxiety arose, and we increasingly turned to ideas about ourselves to assure or soothe ourselves. Thus the mad provided a mirror to see ourselves in. In this regard Kleinman brings an abundance of evidence to show that the newly diagnosed patient in the developing countries who has good access to family and social networks has an excellent prognosis compared to the urban dropout in the West whose isolation is a pathway to chronic institutionalization.

Foucault begins his account by portraying in detail the devastation leprosy brought to Europe, after being transported from the East by the Crusades. Not only were a massive number of leprosariums (lazar houses) built to segregate lepers (and all those misdiagnosed), but it was thought so contagious that people were encouraged to cultivate non ‘good Samaritan’ attitudes, which can be seen in Church rituals claiming the leper’s salvation would be accomplished by their exclusion, and not a helping hand. This theme was intensified further when the plague swept through Europe, to say nothing of various wars. In this atmosphere, madness was seen as a certain kind of wisdom, for they could laugh at the cosmic tragedy and death all around, mocking the pretentious pride seen in some expressions of Christian virtue. So a rather benign attitude may well have been directed towards them; the idea that madness had a ‘reason’ of its own, a sacred form of knowing, often expressed in a form of “naughtiness”. The fear of death was tamed by the lunatic’s laugh; it took the sting out of death. An important point here is the rise in importance of the madman, the fool, and the simpleton as the Renaissance dawned, especially in plays and literature. The wisdom of simplicity or folly was portrayed in the manner we see today in the Peter Sellers movie Being There. In the Renaissance it was Don Quixote.

However, by the late 15th century, leprosy was abating and the leprosariums falling empty; and with that, public attitudes towards the mad, who now held a position of importance in the public psyche, began to change. Prior to that time, the mad were not confined, and many may have lived a wandering lifestyle. If they were a public nuisance, then driving them out of town, or placing them on a Ship of Fools (Narrenschiff) seems to have been preferable than the costs of imprisonment. The practice of entrusting them to the mariners by putting them on ships crossing the seas and canals of Europe, allowing villagers to take pleasure in the sideshow of a ship full of foreign lunatics in their harbour, may have been a reality. However with the recession of the apocalyptic pandemics and the fear of death, a new fear was developing as the Renaissance unfolded, a fear of mass disorder. Machiavelli and his ilk were now advising the sovereign on how to govern the state, so an ordering and manipulation of the population was occurring. Grain was being grown and stored when it was not immediately needed in case of future drought. We’d begun the transition from ruling by kings to governing by governments, and order (or fear of disorder) was central. Foucault points to Durer’s Horsemen of the Apocalypse, a mad fury taking over the world; or the gryllos (half human, half animal) tempting St Anthony in Bosch’s triptych. So the Renaissance saw a growing uneasiness about madness, as it was the antithesis to the self-perception people were increasingly making of themselves and society as rational. (This is why Foucault’s book has been called the history of reason as much as the history of madness.) The Protestant Reformation was an expression of this, and so groups of people who were an affront to bourgeois rationality were becoming more noticeable. The beggars, the petty criminals, the lame, the old, prostitutes, and the insane did not work, or fit well in a society that was being increasingly governed or ordered. Not working or idleness was the essence of unreason.

However, by the late 15th century, leprosy was abating and the leprosariums falling empty; and with that, public attitudes towards the mad, who now held a position of importance in the public psyche, began to change. Prior to that time, the mad were not confined, and many may have lived a wandering lifestyle. If they were a public nuisance, then driving them out of town, or placing them on a Ship of Fools (Narrenschiff) seems to have been preferable than the costs of imprisonment. The practice of entrusting them to the mariners by putting them on ships crossing the seas and canals of Europe, allowing villagers to take pleasure in the sideshow of a ship full of foreign lunatics in their harbour, may have been a reality. However with the recession of the apocalyptic pandemics and the fear of death, a new fear was developing as the Renaissance unfolded, a fear of mass disorder. Machiavelli and his ilk were now advising the sovereign on how to govern the state, so an ordering and manipulation of the population was occurring. Grain was being grown and stored when it was not immediately needed in case of future drought. We’d begun the transition from ruling by kings to governing by governments, and order (or fear of disorder) was central. Foucault points to Durer’s Horsemen of the Apocalypse, a mad fury taking over the world; or the gryllos (half human, half animal) tempting St Anthony in Bosch’s triptych. So the Renaissance saw a growing uneasiness about madness, as it was the antithesis to the self-perception people were increasingly making of themselves and society as rational. (This is why Foucault’s book has been called the history of reason as much as the history of madness.) The Protestant Reformation was an expression of this, and so groups of people who were an affront to bourgeois rationality were becoming more noticeable. The beggars, the petty criminals, the lame, the old, prostitutes, and the insane did not work, or fit well in a society that was being increasingly governed or ordered. Not working or idleness was the essence of unreason.

Foucault says that between roughly 1650 and 1800 the era of the ‘great confinement’ occurred, when increasingly large numbers of these non-productive or Unreasonable (p.83) people were interned in various institutions, many of which were the now empty leprosariums of yesteryear. The Unreasonable had come to occupy the scapegoat position previously held by the lepers; both were defined and contained, a great social controlled. Many of these institutions in Europe were houses of correction or workhouses, attempts to get them working again. Porter (1990) suggests that the nineteenth century be considered the period of ‘great confinement’ for England. Perhaps this was because the transition from sovereign rule to parliamentary governance was more tumultuous in England. As noted above, it was a period when Europe was affirming the sovereignty of its own mode of rationality, and the king’s head was no longer safe. Foucault shows us that ‘reason’ has a particular historical form, which is as parochial as religious rationalizations in other eras and cultures. Thus the Unreasonable, especially the mad, served a special function in this new social ordering process; so we began visiting these houses of confinement like human zoos, so that the bestiality, long suppressed by reason could be seen. (Animal zoos in Europe had only been established a short time earlier.) In other texts Foucault stresses this as an era when people were being subjected to regulatory apparatuses; when the drills from the barracks, the hospitals, the monasteries, the schools were intensifying in use. It was at the beginning of this period of ‘great confinement’ that Descartes gave expression to his (in)famous claim that our primary certainty (and humanity) lies in our rationality; and because of this Foucault sees the mad as being excluded from a shared humanity. Thus there were great cruelties directed towards the mad and by the mad, such as we see in the writings of de Sade.

Although Pinel and Tuke have been heralded as the saviours of the insane late in the eighteenth century, the truth is not so simple for Foucault. Some time before their arrival, legislative and other efforts were made to segregate the poor, the delinquent and the debtor from the frightening bestiality of the madmen in these houses of confinement. So although many madmen were freed from their shackles, and segregated from the non-mad by Pinel, they remained within the walls of confinement. It was more a case of the sane being liberated from the mad. (Critics of Foucault often miss the ‘externalist’ account of history he is providing; he is showing us how these changing attitudes and practices towards the mad are how the state or bourgeois is defining or constructing itself. Economics or governmentality are now becoming more refined, and the criminal and idle are now separable from the mad.) Both Tuke and Pinel report that the animality in the insane protect them from illnesses the sane would succumb to, and hence needed little or no medical care. Thus the doctors entered these institutions not primarily as medics for the insane, but as moral agents for the government, and, in some instances, to appease the locals there were no contagions in the vapors emanating from these places. Having segregated or confined the idle (including the mad) in these institutions, a new fear had developed in the eighteenth century that all this concentrated moral degeneracy (it was being increasingly labeled as immorality) might start infecting others. So psychiatry is born, as much as for any reason, to offer etiologies of the forms madness took, as this would appease the fears of contagion. Their primary focus was not on cure. So it made sense to separate the mad from the others, and then start offering explanations of madness. These accounts began with claims of too much of a particular animal spirit or passion, or conflicts of different animal passions, which in short time become tied to hormones being explored by other branches of medicine. Not only that, by the nineteenth century it was widely believed that as this imbalance or excess of the passions was brought about by moral degeneracy, then morality can be applied to cure madness. At first, this licensed all manner of punishments for immoral behaviour, just as excessive humour theories have justified an assortment of physical therapies such as teeth pulling, lobotomies, hydrotherapy, and rotational therapy, to name a few.

So in the last two centuries, medical practitioners entering the asylum began applying the medical ‘gaze’ upon these folks and developing taxonomies of classification. Now a number of social constructionist writers have noted, following Wittgenstein’s remarks about how the introduction of words into the vocabulary is like setting up the chess board or creating the game we will play, that there has been an accelerating growth of psychopathological words into our common lexicon. Even in the ‘official language’ of psychiatry we have seen a shift

So in the last two centuries, medical practitioners entering the asylum began applying the medical ‘gaze’ upon these folks and developing taxonomies of classification. Now a number of social constructionist writers have noted, following Wittgenstein’s remarks about how the introduction of words into the vocabulary is like setting up the chess board or creating the game we will play, that there has been an accelerating growth of psychopathological words into our common lexicon. Even in the ‘official language’ of psychiatry we have seen a shift

from the 22 diagnoses in the 1917 ‘Statistical Manual for the Use of Institutions for the Insane’, to 106 when the first DSM was published in 1952. By 1968, when the DSM-2 was published it was 182; in 1980 with the DSM-3 it was 265, the DSM-IV in 1994 now taking us to 297. Then in pop psychology there has been an even greater growth, so we have ‘co-dependants, ‘sex addicts’, ‘dysfunctional families’, ‘burnt out professional’; etc etc. These words rush out of professional offices and into the street, making it increasingly difficult for anyone to avoid being stigmatised as abnormal and in need of professional help. Indeed the number of people on welfare due to mental health reasons is growing exponentially in most ‘developed’ countries. Kenneth Gergen calls this a “cycle of progressive infirmity”. On his web site, he suggests that professionals will only be stopped in doing this when we start taking law suits against them for the damage they do in offering these stigmatising labels as identities.

Now, if the social construction of madness is intimately connected with the social construction of ‘normality’ as Foucault’s thesis contends, then this increase might make some sense. In other works Foucault brought a great deal of attention to the invention by the architect and politician Jeremy Bentham of the ‘Panopticon’ in 1800. It serves as a perfect metaphor for governmentality as social construction. This was a prison designed in such a way that the guards could see into the individual cells of each prisoner, but the prisoners could never see when they were being watched. The result was for the prisoners to engage in self-surveillance, and self-disciplining as they knew what they would be rewarded or punished for. Bentham claimed this was the perfect design for governance. Foucault says that we now live in a panopticonian society, where we are all gazing into a mirror of “normalizing judgments’ and self-disciplining ourselves accordingly. Surveillance cameras do not have to be switched on to have this effect. This highly individuates us, and words for “we-ness”, like whanaungatanga in NZ Māori, ubuntu in Zulu, or shimcheong in Korean, have all but disappeared from our language. Foucault described the ‘self’ in Western culture as ‘fabricated’, and late in his career, he described how the Western self was even more individuated by neoliberalism which posited that all of us are entrepreneurs, either successful ones or unsuccessful ones. We noted above Kleinman’s contention that the reason mental health has shown no improvement in its outcomes for at least 50 years, and has worse outcomes for psychosis than many of the poorest countries in the world, was because there were no interest groups benefitting from defining them other than as an individual internalised illness, presumably of a biological type. However, if our economic system, which has been called an ongoing Ponzi scheme by many, is dependent upon understanding human nature only through an individuating internalising lens, then as Martin Luther Kind said, and sadly showed, powerful forces are going to work against constructing madness anew. If, what social psychologists call ‘fundamental attribution error’ is now deeply ingrained in the process of fabricating ourselves, then it is more than psychiatrists, their nurses, and the pharmaceutical companies that are preventing more effective treatments being implemented. But given the ecological disasters this giant ponzi scheme is generating, what if effective treatment of madness helped us regain our sanity?

Now, if the social construction of madness is intimately connected with the social construction of ‘normality’ as Foucault’s thesis contends, then this increase might make some sense. In other works Foucault brought a great deal of attention to the invention by the architect and politician Jeremy Bentham of the ‘Panopticon’ in 1800. It serves as a perfect metaphor for governmentality as social construction. This was a prison designed in such a way that the guards could see into the individual cells of each prisoner, but the prisoners could never see when they were being watched. The result was for the prisoners to engage in self-surveillance, and self-disciplining as they knew what they would be rewarded or punished for. Bentham claimed this was the perfect design for governance. Foucault says that we now live in a panopticonian society, where we are all gazing into a mirror of “normalizing judgments’ and self-disciplining ourselves accordingly. Surveillance cameras do not have to be switched on to have this effect. This highly individuates us, and words for “we-ness”, like whanaungatanga in NZ Māori, ubuntu in Zulu, or shimcheong in Korean, have all but disappeared from our language. Foucault described the ‘self’ in Western culture as ‘fabricated’, and late in his career, he described how the Western self was even more individuated by neoliberalism which posited that all of us are entrepreneurs, either successful ones or unsuccessful ones. We noted above Kleinman’s contention that the reason mental health has shown no improvement in its outcomes for at least 50 years, and has worse outcomes for psychosis than many of the poorest countries in the world, was because there were no interest groups benefitting from defining them other than as an individual internalised illness, presumably of a biological type. However, if our economic system, which has been called an ongoing Ponzi scheme by many, is dependent upon understanding human nature only through an individuating internalising lens, then as Martin Luther Kind said, and sadly showed, powerful forces are going to work against constructing madness anew. If, what social psychologists call ‘fundamental attribution error’ is now deeply ingrained in the process of fabricating ourselves, then it is more than psychiatrists, their nurses, and the pharmaceutical companies that are preventing more effective treatments being implemented. But given the ecological disasters this giant ponzi scheme is generating, what if effective treatment of madness helped us regain our sanity?

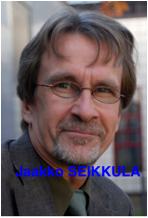

Perhaps the most promising indication of how we might achieve this can be found in a new school of treatment for psychosis that has been developed in Northern Finland by Jaakko Seikkula and colleagues. Follow-ups are showing that about 80% of patients are symptom free, work, and do not take psychiatric medication. Like Martin Luther King, their focus is upon a knot or problem in the social nexus, and so they assemble a team and go to the social network. After all, in most cases of psychosis, it is the family or friends who first ask for help. Wittgenstein once said “The first step is the one that altogether escapes notice”; and the first step in traditional treatment over the past 200 years has been to see the individual on his/her own. They are already estranged from the social network, and we further this. None too surprisingly, the network is often prepared to say “you keep him/her” – and then we wonder why we have long-term chronicity. The problem, as Seikkula sees it, is that dialogue has stopped flowing in this social network, and the task is to get dialogue flowing again. Both the identified patient and their social network have retreated into isolating monologues, the identified patient’s one being largely undecipherable by most, and their social network’s being a monologue about the craziness of the identified patient. Simply by facilitating an atmosphere for dialogue, by maintaining a certain calmness, dialogue begins to flow again. In the first week, the social network may need to meet three or four times, and even sort out rosters as to whom is going to sit through the night with the identified patient – if necessary; but usually within a few weeks, a semblance of dialogue is beginning to be seen again. The outcome statistics Seikkula and colleagues are reporting are truly impressive; and their use of medication is minimal. Those of us with an interest in the treatment of psychosis will be watching this team closely over the coming years. It may well be that whanaungatanga is being re-established in these communities.

Perhaps the most promising indication of how we might achieve this can be found in a new school of treatment for psychosis that has been developed in Northern Finland by Jaakko Seikkula and colleagues. Follow-ups are showing that about 80% of patients are symptom free, work, and do not take psychiatric medication. Like Martin Luther King, their focus is upon a knot or problem in the social nexus, and so they assemble a team and go to the social network. After all, in most cases of psychosis, it is the family or friends who first ask for help. Wittgenstein once said “The first step is the one that altogether escapes notice”; and the first step in traditional treatment over the past 200 years has been to see the individual on his/her own. They are already estranged from the social network, and we further this. None too surprisingly, the network is often prepared to say “you keep him/her” – and then we wonder why we have long-term chronicity. The problem, as Seikkula sees it, is that dialogue has stopped flowing in this social network, and the task is to get dialogue flowing again. Both the identified patient and their social network have retreated into isolating monologues, the identified patient’s one being largely undecipherable by most, and their social network’s being a monologue about the craziness of the identified patient. Simply by facilitating an atmosphere for dialogue, by maintaining a certain calmness, dialogue begins to flow again. In the first week, the social network may need to meet three or four times, and even sort out rosters as to whom is going to sit through the night with the identified patient – if necessary; but usually within a few weeks, a semblance of dialogue is beginning to be seen again. The outcome statistics Seikkula and colleagues are reporting are truly impressive; and their use of medication is minimal. Those of us with an interest in the treatment of psychosis will be watching this team closely over the coming years. It may well be that whanaungatanga is being re-established in these communities.

A further step might be found in one of Arthur Kleinman’s observations. He noticed that the notion “once mad, always mad” was commonly expressed across many cultures. However, in many of those developing countries where people appear to have a better prognosis following a psychotic experience, those close to the person, (relatives etc.), claimed that although it is true that ‘once mad, always mad’, Uncle Charlie was never actually mad. In other words their apparent ‘madness’ never became an established ‘fact’. They were never given an identity (what Foucault calls a “totalizing identity”) as a ‘mad person’. Do we need to diagnose? Now, in the last couple of years it has become desirable for mental health services to initiate and support anti-stigma campaigns. It seems to me that there are two possible thrusts such political campaigns might take in order to reduce the stigma of madness in the community, and make the dream of community integration more realistic. One is to go in the direction we went in opposing racism and sexism, and promulgate a community attitude and discourse that made racism and sexism ‘politically incorrect’. And from what I have seen this has been the major thrust of various state-funded campaigns to end discrimination against the mad. An alternative is to go in the direction gay rights campaigners took – viva la difference! And if you go to the consumer web pages i n the U.S. and Europe you will find some calling themselves “Mad Nation”. Whereas anti-racism and anti-sexism campaigns tend to downplay any differences, stressing the commonwealth of humanity; the gay rights movement has celebrated the differences, highlighting their right to be different. Can madness be celebrated?

This is not necessarily a call to romanticize madness, because for many it can be a very harrowing and miserable experience (although the question will remain as to how much this is due to its cultural reception). But just what degree of eccentricity can we generously tolerate and entertain as a society? Is not a psychotic experience a necessary prerequisite to becoming a shaman in some cultures? Have we not all experienced moments in our lives when some tangential ‘jester logic’ comment has opened our minds to entertain new trains of thoughts?

Can we all celebrate our madness on ‘Mad Pride’ day?

Our greatest blessings come to us by way of madness, provided the madness is given by divine gift – Plato (Phaedrus)

“When we remember we are all mad, the mysteries disappear and life starts to be explained.” Mark Twain

References

Foucault, M. (1964). Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. New York: Pantheon Books.

Jablensky, A., & Sartorius, N., Ernberg, G., et al. (1992). Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures. A World Health Organization ten-country study. Psychological Medicine. Monograph supplement, 20: 1-97.

Jablensky, A., Sartorius, N., Cooper, J.E., Anker, M., Korten, A., & Bertelsen, A. (1994). Cullture and schizophrenia: Criticisms of WHO studies are answered. British Journal of Psychiatry, 165: 434-436.

King, Martin Luther. (1968). The role of the behavioral scientist in the Civil Rights Movement. Journal of Social Issues, 24, 1: 1-12.

Kleinman, A. (1988). Rethinking Psychiatry: From Cultural Category to Personal Experience. New York: Macmillan/Free Press.

Porter, R. (1990). Foucault’s great confinement. History of the Human Sciences, 3, 1: 47-54.

Seikkula, J., Aaltonen, J., Alakare, B., Haarakangas, K, Keränen, J., & Sutela, S. (1995). Treating psychosis by means of Open Dialogue. In S. Friedman (ed.) The Reflective Process in Action. New York: Guilford Publications.